Why I use ambiophonics for mixing and mastering audio

This is a continuation on some of the ideas expressed in my previous post Standing Up To Our Ears

Working with audio involves a randomness that can rightly be attributed to creativity. Professional audio gets confusing because this randomness becomes involved in the evaluation of the tools (as discussed in Standing Up To Our Ears) and techniques. I think this is mostly because many of those same techniques are a blend of creative intuition and scientific principle in which the exact mixture is unknown. The problem is that we are in effect chasing our tails in some pursuits because we rely on scientific research to advance the quality and effectiveness of our technique but we turn around and trust a small sampling of creative opinion or tradition to decide for us what is worthy of merit and what isn’t. I promised an answer in the title and here it is…I use ambiophonics for mixing and mastering because my ears try to trick me and my best defense is to trick them right back.

This idea of tricking one’s ears may seem very non-reference but it is useful. It encourages a modification in our thinking. We think of the Blumlein Stereo setup as a panacea of stereo reproduction. This is understandable as it is the system of choice for the majority of reference audio systems in the world today.

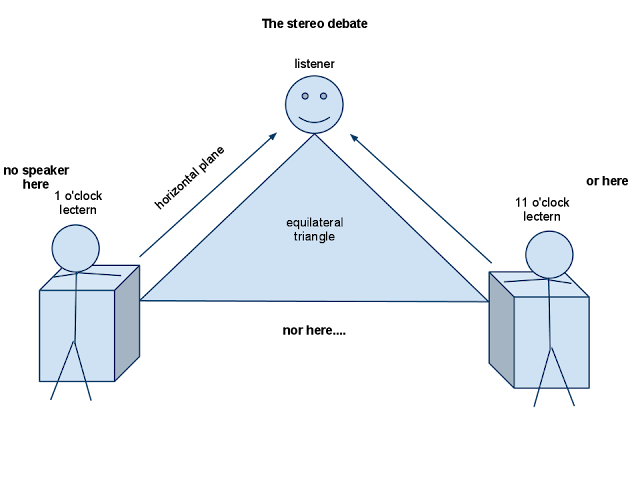

The position of these speakers have little correlation to the position of the sound sources (possibly with the exception of a two person debate with the lecterns at 11 and 1 o’clock), the microphone positions (XY, Mid-Side, etc.) at the time of recording, or the way our ears are actually positioned relative to the source when we finally listen to it all. I’m hoping to impress on you the fact that all recorded and reproduced audio for entertainment or more serious purposes is entirely based on the notion that we can trick our ears into believing they are hearing an acoustic event that isn’t actually happening. For professional work the idea of a reference system is important. A reference system is one that is as much as possible a known quantity. A recorded clarinet on a reference system should sound as much like a naturally occurring clarinet at the point at which it was recorded (the microphone). I think the primary confusion is that the ‘standard’ method of reproduction is so taken for granted that we cease to distinguish between the separate ideas of reference and perception. Reference is what makes sure all the necessary audio content is available to be heard and perception is what makes your ears believe they are actually hearing it.

It all comes back to the ears again. Our hearing defies the concept of reference. We can create a perfectly flat (within reason) speaker and as soon as the audio from that speaker hits our ears all hell breaks loose. The sound bounces off the pinna of the ear as it goes into the ear canal. Because the pinna is at least as unique to each individual as a fingerprint the resulting representation will vary quite significantly. If you doubt the significance of the pinna in our ability to perceive then try this, take a rubber bathing cap and cut small holes where your ear canals open on either side. Put on the bathing cap and notice how difficult it is to distinguish the direction and location of sounds around you. The frequency sensitivity of our ears makes it so we don’t even like the sound of reference (flat) frequency response. At the same time ears can be incredibly perceptive when paired with a well trained mind and presented with convincing information.

Let us consider the effects and idiosyncrasies of some established methods for the reproduction of stereo and surround audio.

The common thread that I hope you see is they all use or are in need of some effect, some trick to convince the ear. I am not interested in criticizing working methods of stereo reproduction. What I am interested in is forwarding the idea that we always have, always are and probably always will be using an effect or illusion to satisfy our ears and our brains into perceiving a convincing stereo image.

Perception is important to critical listening. In a standard studio great pains are taken to ensure that imaging, volume and tonal balance are achieved. This is mainly to increase the perception of the phantom center. The phantom center is an auditory image of whatever audio is common between the two loudspeakers in a Blumlein Stereo setup that appears between the two speakers, directly in front of the listener. It is also a secondary effect meaning that it is not the primary reason that the two speakers are positioned apart from one another. The main reason for that is to achieve a wide sound stage, a large area over which the stereo sound can play out. We have already listed two effects or illusions in the Blumlein stereo system. There are more but that will suffice. I believe stereo reproduction is not naturally derived in any form. Just because a system is readily accepted and widely used does not mean it is more natural.

Ambiophonics is a technique that places the two speakers in a stereo system very close together, only an inch or so apart and pointed towards the listener. Some type of crosstalk cancellation is introduced into the signal path. Crosstalk cancellation in this context is just any device that keeps audio intended for the right ear from being perceived by the left ear and vice-versa.

Some might argue that Blumlein Stereo does not specifically use any sophisticated system to achieve it’s effect and is as a result more natural. To give an equivalent ‘natural’ example of Ambiophonics, one can simply set up a large divider between the two speakers that extends all the way to the listener to the point that it touches their nose. A thin piece of plywood or press-board will do. This barrier will keep audio from the right speaker from effectively reaching the left ear and the left speaker from reaching the right ear. This is a completely functional way to achieve an Ambiophonic effect although it may be cumbersome in modern critical listening environments where a computer usually takes up the space directly in front of the listener. By using a digitally induced effect the partition can be done away with and a few other fixes can be applied to create a more convincing image.

Some might argue that Blumlein Stereo does not specifically use any sophisticated system to achieve it’s effect and is as a result more natural. To give an equivalent ‘natural’ example of Ambiophonics, one can simply set up a large divider between the two speakers that extends all the way to the listener to the point that it touches their nose. A thin piece of plywood or press-board will do. This barrier will keep audio from the right speaker from effectively reaching the left ear and the left speaker from reaching the right ear. This is a completely functional way to achieve an Ambiophonic effect although it may be cumbersome in modern critical listening environments where a computer usually takes up the space directly in front of the listener. By using a digitally induced effect the partition can be done away with and a few other fixes can be applied to create a more convincing image. An obvious concern that has been expressed to me more than once is that mixes or masters created on an Ambiophonic system may not translate correctly to other speaker setups. Once again this is attributing to reference the job that is actually done by perception. When audio is mixed and mastered for stereo release it is based on the practice of referencing other reliable stereo recordings. Blumlein or Ambiophonic speaker setups are merely the method by which we perceive these stereo recordings. The monitor system that is used for mixing and mastering does not affect the signal of the finished product in any way. It merely encourages good choices or bad choices. In short, a good mix in stereo is a good mix in stereo. A good stereo mix will exercise the capabilities of the playback system to their fullest extent. It is my conviction that if the playback system is capable of a more convincing stereo image the resulting mix will actually translate better.

An obvious concern that has been expressed to me more than once is that mixes or masters created on an Ambiophonic system may not translate correctly to other speaker setups. Once again this is attributing to reference the job that is actually done by perception. When audio is mixed and mastered for stereo release it is based on the practice of referencing other reliable stereo recordings. Blumlein or Ambiophonic speaker setups are merely the method by which we perceive these stereo recordings. The monitor system that is used for mixing and mastering does not affect the signal of the finished product in any way. It merely encourages good choices or bad choices. In short, a good mix in stereo is a good mix in stereo. A good stereo mix will exercise the capabilities of the playback system to their fullest extent. It is my conviction that if the playback system is capable of a more convincing stereo image the resulting mix will actually translate better.When I first started experimenting with Ambiophonics 5 years ago I went back and forth many times between it and a Blumlein setup. Eventually I designed a filter using a modification on the RACE method that allowed me to commit fully to using it. It is only after several years of using it that I have a comfortable and theoretical grasp on why it seems to work so well for me. This article is simply a rationalization, a theoretical foundation for why I have chosen to use Ambiophonics for my work as an audio professional. Please do not see this as the end of my argument for or against. See it as the beginning of what I hope to be a useful exploration. In the interests of keeping this posting a reasonable length I will be going into more detail about my specific approach to using Ambiophonics in a critical listening environment in a following article.

1 Response